April 29, 2018. The village of Tokmаk (74 km east of Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan) …Our TV crew arrived too late. We missed a vital episode for our TV documentary: the unique traditional preparation for an ancient wedding ceremony was over.

The star attraction of the episode WEDDING DAY ONE was 18-year-old Radziya Umarova proudly wearing her stunningly beautiful red bridal wedding dress. Her carbon black hair decorated with flowers enchanced the high contrast with her pale face. She was just about to cast the last glance at herselself in the mirror, admiring her just finished in an intricate traditional hairstyle ‘lova’ (‘crow’).

My crew entered a separate room for female Dungans crowded with girls and women. Some of them were sitting on a ‘kana’ (a high Dungan couch) watching the bride in admiration. Little girls were running around, making a lot of noise.

I had to use all possible arguments. including financial, to have the bride’s hair done up again for us. Luckily, the bride had a few hours to relax before the next part of the ceremony. So, Radziya sat still once again on the ‘kana’ and waited patiently while Rosa, a hairstylist, carefully disentangled the ‘lova’ and combed Radziya’s thick black hair again. Silence settled over the room. Showtime!

Within the next hour or so a new elaborate ‘lova’ was made and decorated with silver and gold jewelry as well as even more flowers. Now it looked as if a whole cherry ochard covered her head with blooms.

Needless to say, our crew was delighted – it was the perfect finishing touch we needed for the TV documentary on the traditions of the Dungans which was to be aired on Singapore TV in the fall of 2018.

. . . . .

Moscow. A month before a Singapore-based company had called me. They needed creative and logistic support to shoot a TV documentary about the Dungan ethnic group in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. They wanted to cover their lifestyle and traditions. Also, they insisted that it was of critical importance for the crew to attend a traditional wedding ceremony similar to those held in China centuries ago.

They confirmed their arrival-and-departure dates, so I could start the pre-production arrangements: visas, accomodations, transportation etc. I just wondered how I could get them a wedding ceremony within these dates?

I had never heard of the Dungans before, although for the last few decades I have travelled extensively throughout Central Asia with the National Geograpic and all kind of English and Italian-speaking TV crews and photographers.

I googled the Dungans and discoveved such a breath-taking story that I agreed to join this production right away, despite the risk of failing to come through with the wedding ceremony.

Frankly, I have never regreted my decision. Moreover, I think it has been the real highlight of all my trips to Central Asia as I discovered untapped destinations close to common tourist itineraries and quite an exotic area with charming film-friendly ethnic groups.

. . . . .

First of all, some facts about the Dungans. They are the indigenous people of China. Nowadays most of them live in the Chinese provinces of Shensi and Gansu, where their population exceeds 10 million.

First of all, some facts about the Dungans. They are the indigenous people of China. Nowadays most of them live in the Chinese provinces of Shensi and Gansu, where their population exceeds 10 million.

In 1877, nearly 100,000 Dungans fled China after the decades-long struggle against the Manchu enslavery, violence and discrimination. They crossed the 4000-meter-high Tian Shan Mountains during an exceptionally harsh winter. Only the strongest of them, about 10 per cent, managed to survive the exodus and settle in the Central Asian territories of modern Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Today their population has reached almost 100,000 there.

Importantly, those Dungans were primarily farmers who grew rice and vegetables such as sugar beets, corn, horse reddish, etc. Many of them had brought along seeds of fruits and vegetables which they had grown and sold in China.

The newcomers were happy to find vast territories of virgin land fit for cultivation. They met no resistance from the local nomads. Moreover, the-then Russian Emperor Alexander II granted them the right to live and work there. Nowadays their descendants still remember this imperial ordinance with gratitude.

The Russian Emperor was wise enough to accept those strong and industrious people – all Dungans were Muslims by tradition and abstained from spirits and opium. Moreover, they still retain the leading position in the fruits and vegetables sector in the Central Asia.

Nowadays the Dungans still practice husbandry and horticulture, and trade mostly in the private sector. Their families have huge ochards and vegetable fields. They never use chemical fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides or insecticides.

Also they strictly preserve their ancient culture of holding elaborate and colorful ceremonies for birthdays, weddings, funerals, etc. Some of their schools even have small museums to preserve items that are part of their culture, including embroidery, silver jewelry, traditional clothing, tools, paper cut animals and flowers.

As I found out during our production, modern Dungans still stick to their old traditions, especially, when it comes to their cuisine and dressing habbits which has vanished in modern China. Traditional marriages with matchmakers and elements such as women’s hairstyles and attires worn in the Qing dynasty are still widespread.

Parental authority is very strong in their domestic life. The mother does not get up for fifteen days after the birth of a child. A mullah gives names to children the day after they are born. Circumcision takes place in the second week.

When a girl is married she receives a rich dowery. Most Dungans are family-oriented and have many kids. However, currently divorce happens more and more often, mainly among the young generation: modern women feel more independent and often initiate the separation.

When a death occurs, a mullah and old relatives get together to recite prayers. The deceased is wrapped in white linen and then buried, but never cremated. After the interment, the mullah and the elders partake of bread and meat. Three months later the widow may re-marry.

. . . . .

Our trip was tough, but we were lucky. We covered nearly 400 km from Almaty (Kazakhstan) to Bishkek (the capital of Kyrgyzstan) travelling mostly accross dry steppes.

We spent two nights in the Dungan villages of Sortobe and Masanchi located near the boder of Kazakhstan.

Thanks to a young diplomat, Janibek, from the Kazakh Foreign Ministry in Astana our crew obtained media accreditation and special permits quickly, so we crossed the border zones with no hindrance.

We also spent three more nights in Bishkek and visited the neighbouring Dungan villages of Tokmak and Alexandrovka in Krygyzstan.

. . . . .

Our 7-day program was successful thanks to the support of both the Kazakh and Kyrgyz Associations of Dungans. Indeed, these people were extremely helpful in meeting all our requirements. We never expected such hospitality from our film-friendly hosts who were as a rule someone’s friends or distant relatives.

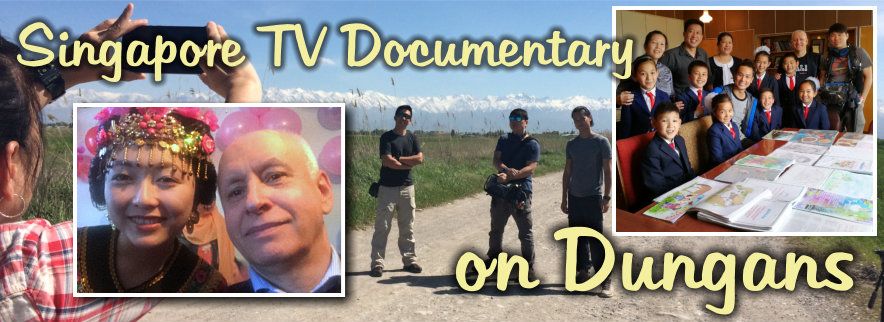

Our crew (left to right): sound engineer Brando Wong Lum, cameraman Koh Soon Sng, exec producer Ng Bee Yian, TV host Chen BangJun

In both countries we interviewed the chairmen of the Kazakh and Kyrgyz Dungan Associations, as well as the Director of the Museum of Dungan history.

Meeting with Hussei Shimarovich Daurov (at the head of the table), the Chairman of the Dungan Association in Kazakhstan

Meeting with Karim Lemzarovich Khanzheza (third from the right), the Chairman of the Dungan Association in Kyrgyzstan

The Mosque in the village of Ken Bulun was crowded with over a hundred men who attended the Saturday service, after which they enjoyed a feast, while their girls and women were busy in separate premises cooking or taking care of their kids.

Our Singapore crew was also present at a Dungan language lesson at a Dungan high school.

School students use Dungan-language textbooks and dictionaries published in post-Soviet times. I also saw Dungan-language weekly newspaper published since 1932.

The Dungan dialect is different from the Chinese mandarine spoken in Singapore. That is why the Singapore crew needed me also as a Russian-English interpreter, since all the Dungans speak Russian as well as their local Kazakh or Kyrgyz languages. Sometimes the Singapore producer also needed my on-camera comments in English.

We interviewed two elderly Dungan women, each of them was a famous embroiderer of traditional clothing and decorative items in Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan.

Some of their works are real masterpieces made for major events, such as weddings, funerals, or religious confirmation.

In Bishkek we inteviewed a Dungan family who runs a small 2-star hotel. Their teenage daughter, who spoke fluent Chinese, became the life and soul of the party when our crew went out for dinner.

We interviewed two beautiful Kazakh Miss Dungankas who had won national beauty contests. The meetings were very brief as they were married now and, no doubt, had to leave in a hurry to take care of their small kids and husbands. Or maybe they just did not have much to say.

Lastly, we always combined informative meetings with enjoyable variety of healthy and tasty food in Dungan restaurants and with families. Hosts always treated us to plenty of food, tea and soft drinks. And, yes, the food was served with traditional chopsticks.

Bishkek – my most enjoyable and memorable meeting. As it often happens, unplanned improvisations are most rewarding. For some unknown reason we had to change our itinerary: our local Dungan guide suggested some new place to pop in.

We entered a big yard around a large beautiful mansion. A charismatic patriarch, Sharip Gubarovish Mashukhei, the former Minister of Fruit and Vegetable Sector of Agriculture in Kyrgyzstan, introduced his charming family. We joined the company of his elder daughter Rimma, a psycologist, her younger sister Zamira, an English language teacher and his grandson Abilkhan.

Somehow unnoticeably, we all fell under the spell of these high society Dungan city girls with bright eyes, friendly smiles, great sence of humor, genuine openness and a bit of naïve curiosity. They were at ease with both sophisticated small talk and the Internet to google if they needed more information.

A bit later Sharip Gubarovish proudly explained to us that his Abilkhan was the winner among children at the Olympics of Mental Maths held in Kazakhstan and Thailand. Mental math is the ability to do calculations in one’s mind without gadgets or writing down figures. It has become popular among small kids and teenagers in Asian and Arabic countries.

Abilkhan came with his 9-year-old classmate who was a chess master and the winner of world chess tournaments. Rising stars of a modern Dungan generation…

It was one of the most heartfelt meetings throughout all my trips to the Central Asia. When we left this paradise of cordial hospitality, I felt both sad and happy.

. . . . .

WEDDING DAY TWO:

The next morning we entered again the same separate room for female Dungans crowded with girls and women. Radziya was sitting again on the ‘kana’. She was all smiles looking like a fresh rose, despite the night she had to sleep in a seated position in order not to ruin her intricate hairdo ‘lova’. Little girls were running around like yesterday, making a lot of noise. And the ladies greeted us as good old friends.

Soon a woman arrived from the house of the groom. She got up on ‘kana’ and spread a large red kerchief over Radziya: a shower of nuts and candies rained down on the bride’s head. The woman whispered something. She wished the bride many kids, happiness and prosperity for her new family.

Immediately all the little girls and women dashed to grab the nuts and candies. Each of them wanted to snatch their own piece of luck: the hope for kids, happiness and prosperity. Some of them smiled showing us their handful of trophies. Our crew was happy too: what a dynamic scene!

Then the woman covered Radziya’s head and face with that red kerchief – from then on the bride was no longer a girl, she would be a married woman.

We had to leave the room to enjoy a meal in a huge yard under a roof. Meanwhile Radziya put on a new red dress brought to her by the woman with the kerchief.

When we returned to the room, Radziya was all smiles and taking selfies with all her girlfriends, relatives and kids. She looked like a very happy doll…

We did not see what was going on with her groom at that time. I asked her elder sister Rosa, who was busy attending to Radziya and yet always graciously helped us and found time to chat in a very open and supportive manner. I think we liked each other.

Rosa explained that according to an old Dungan tradition, the groom had to remain composed with his bestfriends and generally all men, including male neighbours. The male party was supposed to make crude jokes with the groom. Sometimes they even shoved him slightly or teased with irony to cheer the goom up. The groom may thank them or defend himself in a playful manner.

Meanwhile, the festive spirit in the house was high. Dozens of girls and women of all ages were wearing beautiful costumes embroidered in multicolored silk. There was an air of general excitement. Everybody was dressed up, especially children and even men.

Soon a large group of girls and women came in the yard. They were the groom’s relatives. They sat down around a long separate table set with all sorts of food. They ate almost nothing. As I understood, they looked around and discussed every detail, including a huge heap of wedding presents piling up next to them.

At last, the groom Aziz arrived at noon with his bestfriends and male relatives. He was dressed in a dark suit and white shirt with a broad red ribbon across his shoulder and one hip. This 21-year-old man was obviously very nervous. However, he knew his role: he made many energetic bows to all the bride’s relatives and friends of all ages, even to little girls. They were ceremonial three-fold bows to each person. And he coped well – bowing separately to the bride’s father and mother, as well as to old grandmothers who were sitting apart in various places, to all sisters and even to neighbors.

Each time the groom put his hands together, raised them above his head and made a low bow without parting his hands. Within a few minutes he made about 150-200 bows.

Quite an exercise!

Then Aziz and a large group of his male friends were ushered into a separate room. Then young girls from the bride’s family started to run back and forth willingly with large plates of food. Their eyes were glittering with mystery: apparently that was how the future brides and grooms met.

At noon, a car decorated with flowers and balls drove into the yard. The back seat was covered with a beautiful blanket. The uncle of Radziya wrapped her in the blanket and carefully put her on the back seat of the car.

Then everybody stood up: Radziya was leaving her hospitable home for the groom’s house.

Her sister Rosa told me that in the past all the relatives of the bride used to cry when the bride and the groom were leaving for the groom’s house. Now no one cried, everyone looked cheerful in anticipation of the feast.

Rosa told me lots of interesting things that morning. But that is another story…

We had to pack and leave for the airport. Goodbye, dear Dungans!

. . . . .

When our crew left Bishkek for the airport, we stopped near the montains to shoot the final on-camera comments and draw our conclusions about the trip.

As far as I remember, I said:

“I love this place – lots of sunshine and fresh air. I wish I could live here among the Dugans. I admire these friendly and hard-working people with sincere uncluttered minds. I admire the way they preserve their history, their exotic traditions and their amazing hospitality.

It seemed to me like a time machine had transported me back to my youth in the years in the Soviet socialist society, when we all trusted and helped each other selflessly, since we believed that “it is better to have 100 friends than 100 Rubles.”

Furthermore, I had felt like being at a wedding ceremony in ancient China. The only thing that reminded me of modern times was the crew nearby and selfies taken non-stop by the Dungans of all generations.

I enjoyed this trip a lot. I enjoyed visiting the big clean Dungan houses, where I left my shoes at the doorstep like everybody else. And I experienced a very special aura in those houses, like at my parent’s home.

Sometimes the roads were bad, but, interestingly, I saw many more Audis, BMWs, Mercedez or even Porches of the lastest models in the Dungan villages than in the big cities there.

I liked their vast fruit and vegetable fields and their affluent villages. I also enjoyed their food, so healthy and harmonious.

By the way, life expectancy is higher there. If people live longer, obviously, they are happy.

In short, I’ll definitely come back to see my Dungan friends again”.

P.S. Three months later I am still in touch with some of my new Dungan friends. In May and June during the Ramadan our correspondence was not very active. No wonder, how could one be active for four weeks in heat of the summer without water and food all day long?

But some of my Dungan friends even stayed up all night to watch the 2018 FIFA World Cup games despite the 3-hour time difference with Moscow.

I have kept some of the most revealing Viber messages, including: “Today my father invited me to visit him and he insisted that we secretly shared lunch… He told me that he cared much about me and that I needed to be strong to work hard in my office and take care of my family during the fast.” I really appreciated this very friendly and sensitive revelation.

I am so glad for the strong bonds of trust and friendship with all my Dungan friends.

Eugene Zykov

Producer, Fixer, Owner

Russian Film Commission